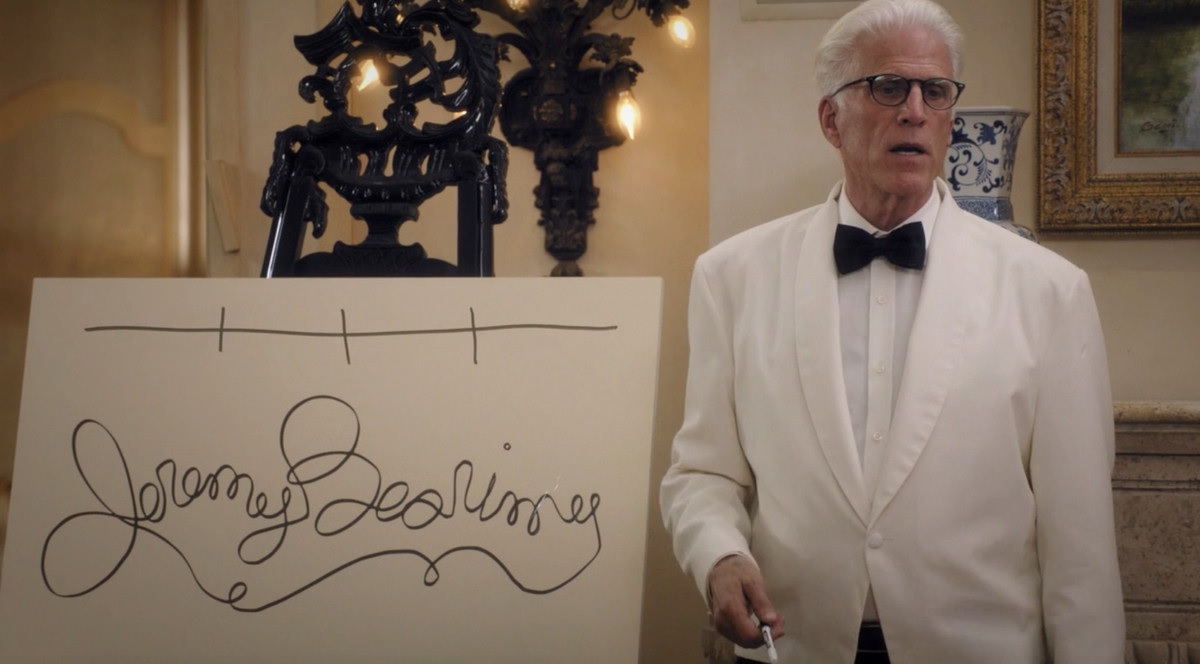

The Good Place,Michael (Ted Danson) explains that time is not a line but loops and squiggles that resemble the name Jeremy Bearimy written in cursive.

TH 6317 The Interpretation of the History of Israel

This course studies the history of how Israelites and their successors have articulated understandings of the meaning of history and particularly the role of God in salvation history. The period from the national origin of Israel through the Babylonian exile is studied from a wide variety of viewpoints. These viewpoints include early national hymns, the Deuteronomists’ retelling, the Chroniclers’ retelling, apocalyptic retellings, Midrashic retellings, the modern history of religions school, archaeology, other historical-critical methods, and postmodern contemporary-critical methods such as post-colonial interpretation.

| Keyword | Premodern | Modern |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptic | The Bible means more than / other than it appears to mean. There are hidden meanings. | The original authors intended to communicate as clearly as possible to the original audience. If the meanings are obscure to us it is because we don’t have a time machine. |

| The stories are perfectly consistent | The details of the stories and laws do not contradict each other. If there appears to be a contradiction, see rule 1. There must be a hidden meaning or distinction. | It is natural and expected for the many authors and editors of the Bible to have different understandings of facts and theological principles. If there is a contradiction it indicates multiplicity of authorship. |

| The canon is a perfect whole | Any part of the Bible may be used to interpret any other part of the Bible. Like the movies in the Star Wars saga, the books of the Bible belong to one coherent series and may be mutually illuminating. | Until proven otherwise, the authors of different books of the Bible did not presume or even agree with other authors now in the Bible. Much as Avatar and the Smurfs are only superficially united by the common element of blue people running around in the forest, the books of the Bible may be only loosely linked by Israelite history. |

| The characters are morally perfect | God and the heroes of the Bible never made any mistakes. If they appear to have made mistakes, see rule 1. | The Israelite authors did not expect God to follow later theological principles such as omniscience. They did not mind portraying their heroes as flawed. |

| The message is perfectly consistent with my religion | The Bible teaches my religion and my religion follows the Bible. | The beliefs and practices of any religion developed over time. Since much time separates the ancient authors from religions today, substantial differences are expected. The interpreter should overcome the tendency to project later theological or religious developments onto earlier texts. |

| Relevant | The Bible is relevant to me. It is about me and my times. It is written as instruction for me and my community. | The Bible is relevant to the original author and audience. It is about them and their times. If it does mean anything to you then you should overcome that bias to discover its original meaning. |

| Divine | The Bible is ultimately from God and authored by God. One might think this is the earliest and most fundamental assumption that leads to the other three, but historically it is the last to be asserted. | The Bible as we have it was composed and transmitted by humans in human language, with human literary and rhetorical devices, and other cultural assumptions. |

The “four assumptions” of cryptic, relevant, perfect, and divine are taken from James L. Kugel, especially The Bible as It Was. The different implications of “perfect” are here expanded. The contrasts that Kugel draws between premodern and modern interpretation assume a time when there was a Bible of some kind to be interpreted. Similar methods of interpretation occur within the Bible itself, particularly later passages and books interpreting earlier passages and books. This can be called intertextuality or inner-biblical interpretation. For more on this see Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel.

| Keyword | Modern | Postmodern |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Meaning is generated by the author and stored in the text for the reader to recover. (authorial intent) | Meaning is generated by the reader’s engagement with the text. (readerly interpretation, reader-response) |

| Multiplicity | For any one text (single author and historical context) there is only one meaning. When there are different meanings in the text that indicates different authors and editors. | There are many readers so there are many meanings. |

| Context of the interpreter | The interpreter must be objective and prohibit any influence from the interpreter’s own life, times, and beliefs. | It is impossible to be objective so the interpreter should embrace her subjectivity. Our experiences as individuals and members of groups influence our interpretation and that is good. |

| Diversity | Gender, class, ethnicity, faith, and experience of the interpreter are irrelevant to recovering the ancient authorial intent. Biblical scholarship should not reflect any of these corrupting influences. | Different perspectives on the Bible from other groups enrich our understanding of the meanings of the Bible by showing us what we could not have seen ourselves. Even by their own standards of focusing on the authorial intent, homogeneity in bibilcal scholarship (privileged white males) has missed major themes that were easily apparent to others. |

The Good Place,Michael (Ted Danson) explains that time is not a line but loops and squiggles that resemble the name Jeremy Bearimy written in cursive.

As the modern understanding of history emerged, it became clear that the Bible was not history in the modern sense. One response is to insist that the Bible is historically accurate in the modern sense of history. This response, called Fundamentalism, is strongly rejected by Catholicism. Fundamentalism is not a return to premodern understandings of the Bible as history. Premoderns believe the Bible is true in the premodern sense of the stories are true—they convey truth. Fundamentalists believe the Bible is true in the modern sense of history as factually verifiable—the Bible is a Polaroid picture of events that happened exactly as described. Furthermore, fundamentalists believe that the Bible, being a source of objective factual information, can be used to derive secondary facts not intended by the ancient authors. For example, fundamentalists believe the genealogies in the Bible can be used to argue against science that the earth and all forms of life are only a few thousand years old. No Israelite ever intended to argue that the earth is young; on the contrary the ancient-ness of God was praiseworthy. If they could have conceived of a universe billions of years in the making, as twenty-first-century science helps us do, they surely would have embraced it.

Catholics and most Jews and Christians today believe that the truth of the Bible is compatible with modern human reason, including modern science (which says that the earth is much older than a few thousand years), and modern history (which notes many chronological contradictions in the Bible). Furthermore, modern reason adds new depth of understanding to the truth of the Bible. Modern methods allow us to study not only the content of the stories, but the historical context in which they were first expressed. Catholicism first embraced these methods in 1943, and most monumentally in 1965 with Vatican II’s “Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation” (Dei Verbum). These methods are collectively called the historical-critical methods, and include source-criticism, text-criticism, and pretty much every other something-criticism. They are critical not in the sense of attacking the Bible, but in the sense of using reason to discover truth beyond taking things at face value.

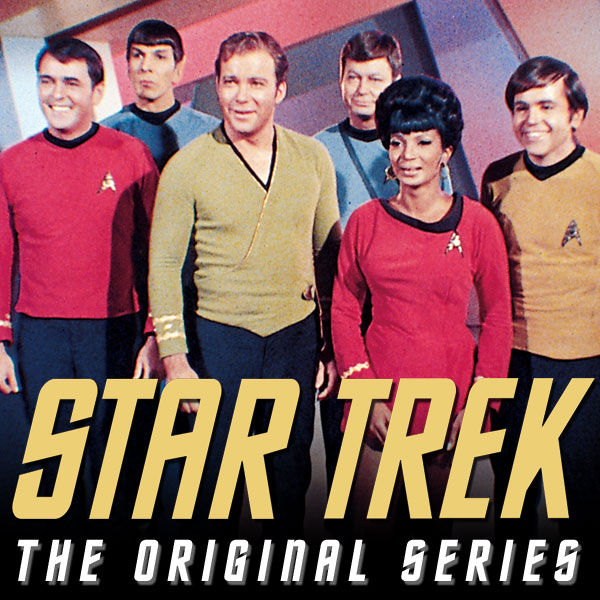

Modern historical-critical study of the Bible argues that much of the Bible reflects a time of composition much later than the time when the story is set. The story of the funeral of Moses was not written by Moses (as fundamentalists would insist), but during the Assyrian crisis. Understanding the Assyrian crisis does not disprove Deuteronomy, but rather casts significant light on how the Israelites articulated their understanding of their covenantal relationship with their God. Think about “Star Trek” the original series from 1966-68. It would be silly to argue whether it is “true,” for insisting that it is not true would trivialize its resonanace with American culture. More interesting questions, or questions that illustrate the role of the historical-critical methods, are the following:

Star Trek may not provide accurate historical information about the 2260s (when it is set), but it does provide information about the 1960s, including the state of TV making (sets and special effects), women’s fashions (short polyester skirts and haircuts), and so forth. More importantly, historical information about the 1960s (not the 2260s) is essential for understanding Star Trek. If one knew nothing of the Cold War it would be meaningless that a Russian and American were working together. If one knew nothing of the civil rights struggle it would be meaningless that a black woman was an officer on a space ship. If one knew nothing of Loving v. Virginia (the Supreme Court ruling that overturned laws banning interracial marriage) it would be meaningless that a white man and black woman kissed. Getting back to the Bible, I hope we can quickly move past whether the stories in it are true. They are true in at least one sense, even if they are rarely true in the Polaroid-picture sense. They tell us something about the history of Israel, even if not about the time in which the story is set. The study of the history of the ancient world using modern human reason will create much meaning, even if it challenges the Polaroid-picture meaning.

Here is another illustration of the contrast between ancient and modern conceptions of the Bible and history, this one from a Jewish perspective.

“In regard to history we must take care to distinguish between biblical history and the history of ancient Israel. The first category is what Scripture presents to us: the view of biblical authors as to the what and—more important for them—the why of the significant events in Israel's career. The second category—supposing it were a prime interest of the biblical ‘historians’—may have been as difficult for them to recover as it is for us.”

Herbert Chanan Brichto, “On Slaughter and Sacrifice, Blood and Atonement,” HUCA 47 (1976) 19-55, here 51.

Examples

Mark A. Leuchter and David T. Lamb, The Historical Writings: Introducing Israel’s Historical Literature. Introducing Israel’s Scriptures. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2016.

Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel.

James L. Kugel, The Bible As It Was.

James L. Kugel, How to Read the Bible.

Vatican II, Dei Verbum: The Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation. vatican.va