What was Jesus doing for those three days while my mother was making me polish silver, furniture, and baseboards? Why was I never told, as a child, the traditional answer, “Jesus was in Hell”? Perhaps it relates to changing definitions of Hell. If Hell is the place of shades, the underworld, Sheol or Hades, the place where ALL go upon death, then of course Jesus’ death entailed a journey to the underworld. If Hell is a place of torment for sinners, then Jesus shouldn’t be there. If Hell is the absence of God, then by definition the Son of God could not be in such a state or place. Furthermore, if Hell is the eternal separation from God, it would make no sense to remove souls from it. We are going to have to be careful with our definitions and assumptions.

The Harrowing of Hell, and the variations in the tradition, will lead us through several theological questions related to eschatology.

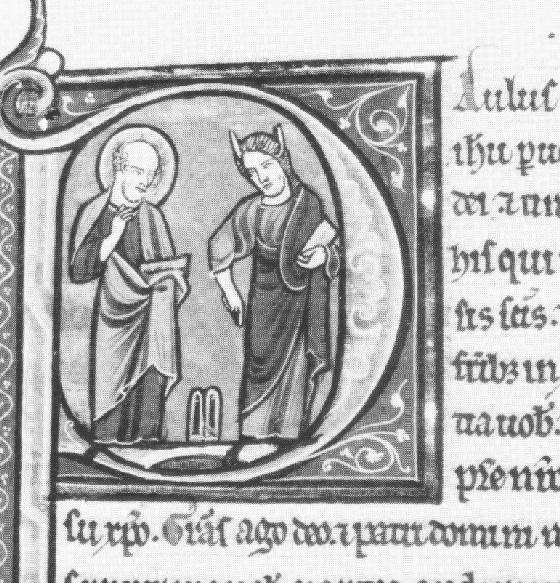

We are going to look at variations in the tradition, but several features are common or assumed. The basic idea is that Adam’s sin established a contract or a charter for Death (capitalized here because it is personified, sometimes Hades). Adam, and all the sons of Adam contained within him, sin, and therefore are subject to Death. Sin is the ultimate and only real cause of death. Some take that for granted. The image or implication already appeared in this course, in Hezekiah’s prayer, “you have held back my life from the pit of destruction, for you have cast all my sins behind your back” (Isaiah 38:17). Some Christian writers and artists portray Adam signing a contract with Death. (See Michael E. Stone, Adam’s Contract with Satan: The Legend of the Cheirograph of Adam. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.) Meanwhile, Satan helped Death to document and cause sin. For a few thousand years that system worked well and everyone sinned and everyone was handed over to Death. Then came Jesus, whom Satan caused to be killed, but had failed to document even a single sin. Sometimes the exchange between Satan and Death is rather comic, like two stooges deciding whom to blame for a screw-up. Jesus insists that Death has no right to hold Jesus because Jesus did not sin. The story could stop here with an explanation of how Jesus came back to life. However, the significance of the Resurrection, for Christians, is not just what happened to Jesus but its implications for all of us. Death violated its mandate, and therefore the whole agreement is cancelled, like a bar losing its liquor license after a single violation. Death no longer has final authority over sinners.

There is more variation in what happens next. All seem to agree that at least Adam and Eve resurrected along with Jesus on Easter. It is not that they are more worthy than Abraham and David, but they are the foundational tokens of the whole arrangement with Death. Many others may or may not have also been taken. Especially the way Ephrem tells it, it is rather disturbing how “not yet” the resolution is. Jesus is essentially persuaded to extend the mandate of Death and the work of Satan just to give them a sporting chance.

In Christian art, the breaking of the contract with Death (Cheirograph) is often placed at the baptism of Jesus, rather than the death and resurrection. The implication seems to be that at least for the ordinary follower of Jesus, baptism is the immersion into the underworld and return that most signifies our own resurrection. Of course the implications of the necessity of baptism for salvation will have a long and difficult history.

Notice the almost universal agreement that Adam and Eve are first in, first out.

One of the tricky things about my job is to distinguish the meaning that comes with retrospect from the history of interpretation, from the meaning that would have been understood by the original audience. On the one hand, the story of the harrowing develops over hundreds of years. On the other hand, it certainly does seem that Matthew 27:52 would imply something along those lines. Perhaps it was originally just emphasis on miraculous power and significance, without the theological implications filled in. Also, related to my question of, “why don’t we talk about this anymore?” note that the Nicene Creed is longer than the Apostles’ Creed in all ways except taking out, “He Descended into Hell.”

The basic story is probably somewhat older than this text, and it also has some later developments. I think this composition can be dated to the fifth century. It dates the first coming to the year 5500 of creation. That would seem to fit with the expectation of Irenaeus and others that creation would be complete after 6000 years. Thus the author seems to assert a significant eschatological change in the year AD 500. The text must have been written before then, probably within a lifetime before since people generally calculate the end in their own lifetimes.

Here are some reminders about the figures assumed in the Gospel of Nicodemus.

Ephrem is probably the most famous figure from Syriac Christianity. Roman Catholics tend to think of the spread of Christianity occurring from east to west through Peter and Paul, but there were other apostles, and there are no less plausible traditions about Thomas traveling all the way to India. Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic, Jesus’ first language. Syriac-speaking Christianity extended from Turkey to India, and developed its own very interesting and beautiful literature and theology. Recall that Babylon was a major center of Jewish learning in the period (leading up to the Babylonian Talmud), and there are many interesting and understudied issues of Jewish and Christian co-existence in Mesopotamia. Ephrem himself lived in the fourth century (306-373). The Hymn we are reading comes from a cycle called, “Songs of Nisibis” about the fall Nisibis to the Persians.

Besides its own beauty and insightful connections between the Old and New Testaments, I am interested in this account for how it compares to the Gospel of Nicodemus on the issue of Already/Not Yet. Whereas the Gospel of Nicodemus asserts more happening with the first coming (more resurrected, Satan bound), Ephrem views the already as a symbolic pledge of the not yet.

Dante (1265-1321) is credited with the dawn of the Italian Renaissance. The Renaissance carried with it a greater awareness and appreciation of pagan philosophers and poets, and even the Arab philosophers who were doing amazing things in Muslim Spain. Dante will be troubled by the teaching that everyone who is not a baptized Christian is of necessity in Hell, especially as Hell came to be understood as a place of eternal torment. Later Christians will continue to work on the problem of salvation outside the Church.