Spectral RTI is the integration of spectral imaging and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI). If you are doing spectral imaging already, the question is whether the addition of RTI is worth the time. If you are doing RTI already, the question is whether the addition of spectral is worth the money. If you are doing both separately, there is no question that the integration will surpass the sum of the parts in quality, time efficiency, and cost effectiveness. Intermediate options cover a range of texture quality, including a few raking angles (not interactive RTI), minimal RTI (around 30 angles), or high-resolution RTI (around 50 angles).

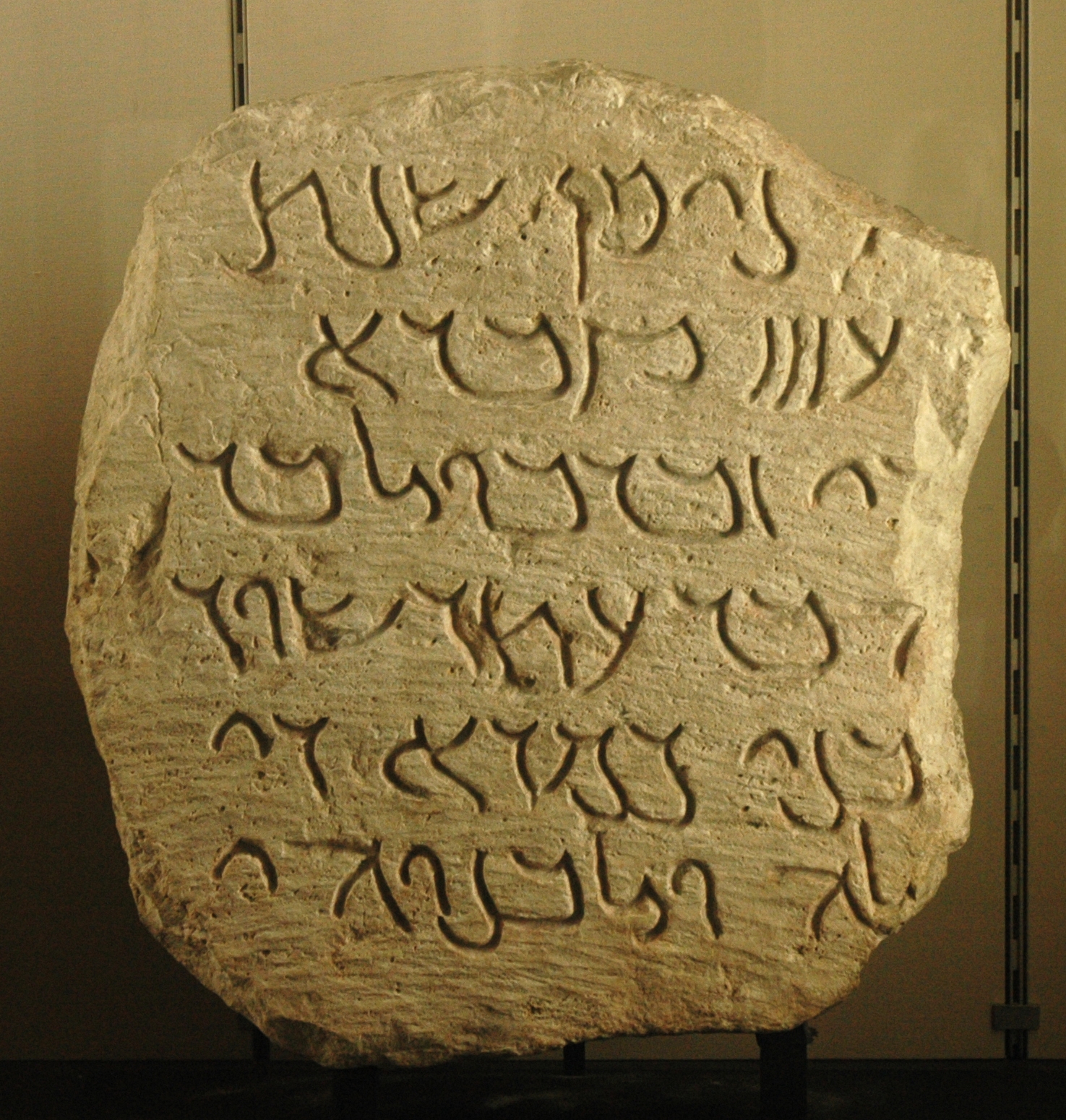

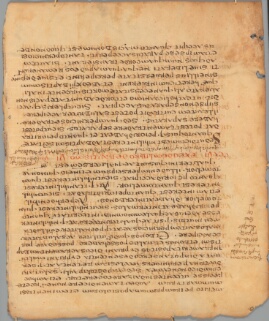

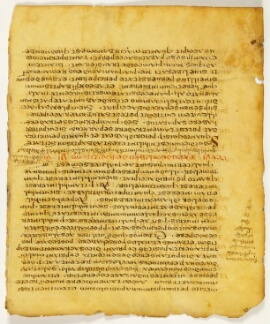

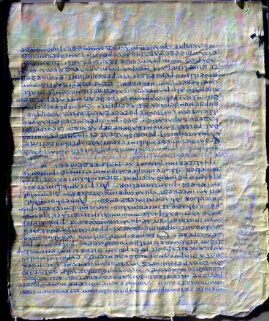

The benefits of adding RTI fall into the areas of the benefits of capturing texture data and the benefits of adding interactivity to the user experience. The importance of texture data is clearest for cultural heritage objects in which texture is the primary conveyor of meaning, such as cuneiform, inscriptions, and coins. Additionally, dry-point notation was the Medieval equivalent of using a pencil in a library book. By pressing with a sharp point without ink, scribes could make notes to themselves without defacing the manuscript. In each of these cases with homogenous materials, a diffusely illuminated image might be completely indecipherable. Texture can be important to recovery of text from parchment if the ink corroded the surface of the parchment, such that the outline of the letter can be read even if the ink is completely missing. Texture can also aid recovery of text by showing the scribal scoring lines (and hence where text should be) and the shrinkage, warp, and cockle that would affect the reading. Texture can also hold clues as to the brush strokes or even fingerprint of an artist. In general, the capture and rendering of texture gets at the "feel" of an artifact and helps address the criticism that there is no substitute for first-hand experience.

The second benefit of RTI is interactivity. RTI images are dynamically relightable, which means the user can move a virtual light around the object (even to positions not physically captured) to see the movement of highlights and shadows across the texture of the artifact. This interactivity can be beneficial for discovery in that human perception benefits from movement and is adept at piecing together meaning from a sequence of images. Interactivity is also beneficial for conservators of a collection who would like to exhibit the experience of a cultural heritage artifact that cannot be adequately experienced behind glass (or safely taken out from behind glass). Interactive images can be exhibited in a museum kiosk next to the original, or on the website promoting the exhibition to potential visitors. For example, RTI images have greatly enhanced the exhibition of the coin collection at Palazzo Blu in Pisa, vcg.isti.cnr.it/PalazzoBlu. Similarly, a teacher can appreciate the value of offering students an experience of an artifact.

The cost of adding RTI comes as a balance of time and equipment. The minimal cost in equipment is a hand-held flash with radio (not infrared) trigger. Even with the addition of an extra rechargeable battery pack and laser distance finder, the equipment budget could be less than a thousand dollars (USD). The hand-held flash method requires manually positioning the flash at about 40-50 points around a virtual hemisphere. Even with practice, this could add five minutes to the capture time. The hand-held flash method also requires light position calculations for each object sequence, adding another five minutes. A dome or arc could automate the sequence to take negligible effort. The primary time constraint is the time required to transfer the data, which for 56 images at 50 megapixels each is close to three minutes. An automated arc or dome for RTI capture could be expected to cost five to eight thousand dollars.

An intermediate step between diffuse-only captures and full-RTI captures is the addition of raking illumination, which can be handled by the same software and techniques for Spectral RTI. Raking illumination shows texture by allowing light from only one low angle. RTI captures can be thought of as a complete set of raking illumination captures, such that the capture team does not need to worry about the optimal angle, and the user can experiment with different raking angles interactively. However, if expense in time and equipment prohibit a complete set of raking captures for RTI, even a small set of captures from a few low angles can be greatly beneficial, especially if care is taken at time of capture to pick the most beneficial angles. In the past, spectral raking images were created by moving a spectral LED bank to a low angle and repeating a complete capture set. With the software used for Spectral RTI (even if the data is not complete RTI), the chrominance information can be used from the diffuse captures, and a single flash or white LED can be used to capture the luminance information for texture. This saves substantial time in moving and calibrating equipment, and avoids error from different wavelengths coming from slightly different angles.

A note on terminology: terms are used loosely and inconsistently when it comes to spectral imaging. If one adopts the definitions used here, then the "spectral" of Spectral RTI is multi-spectral imaging. The term "spectral imaging" can encompass any form of imaging in which attention is paid to wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum within or near the range of light visible to humans, beyond simple color photography. Thus, infrared imaging could be considered spectral imaging because it steps outside the convention of photography representing the range and resolution of the three human color receptors. It would not, however, be considered multi-spectral if it is rendered as a monochrome image not meaningfully combined with other wavelengths, such as the visible. The term "multi-spectral" is here used to refer to a number of discretely resolved wavelengths greater than three (the natural wavelength resolution of human perception). The methods of multi-spectral imaging as of 2019 (narrowband LED illumination with a panchromatic sensor and apochromatic lens) effectively limit the number of discrete wavelengths of reflected light captured to about 20. The narrowband illuminators are not so narrow that many more wavelengths could be helpfully distinguished. A different capture approach entirely (line at a time capture with a diffraction grating) allows finer resolution of reflected wavelength, well into the hundreds of bands. Thus, an imaging system current to 2019 can be called "multi-spectral" if it resolves a number of wavelengths expressed in two digits, and "hyper-spectral" if it resolves a number of wavelengths expressed in three or four digits. However, it is not necessary to agree on terminology. The current ability to combine spectral and RTI has been proven with the capture system that resolves double-digit numbers of reflected bands (in addition to transmitted and fluoresced bands).

The most sensational benefit, which has driven spectral imaging from its earliest form in 1844 through the dawn of digital multi-spectral imaging with the Archimedes Palimpsest Project, has been the rediscovery of unreadable text. Thus, strokes of erased or damaged writing in manuscripts that cannot be discerned with the natural color range and resolution of the human eye can be distinguished with multi-spectral imaging. The ability of spectral imaging to distinguish visually-similar materials of different spectral signatures also has benefits in the area of discovering forgery or tracking the work of conservators who “touched up” paintings. The less sensational, but not least important, benefit of spectral imaging is the ability to capture color far more accurately than conventional color photography. Cameras designed to capture three colors in an instant only roughly match the three color sensors of the human eye, and do so at the expense of distorting filters. Megapixel for megapixel, the spatial resolution of the panchromatic sensors used in spectral imaging vastly outperform cameras designed for fast color photography. Color matching across cameras, screens, and printers relies on subjective human color matching, which can be difficult to trace across time or collections. When accurate color information is processed, conservators can compare images taken across time and know that differences in appearance indicate difference in the material of the object, not the photography.

Spectral imaging can be automated to be done very quickly. Again, the primary limitation is the time required to push data from the camera, roughly three seconds for each of up to 20 reflected wavelengths, plus transmitted and fluoresced wavelengths. The major costs come in the form of equipment. A complete multi-spectral imaging rig including panchromatic sensor (camera), apochromatic lens, narrowband illuminators, thin-panel transmitted light source, and fluorescence filters could easily reach $100,000. Even rental costs would be measured in the thousands of dollars. Options for lowering the cost of entry to spectral imaging include making slight (removing the built-in IR block filter) or major (removing the Bayer filter) modifications to a Canon or Nikon digital camera. In some ways the cost challenge of a panchromatic sensor is not the complexity to build but the lack of a market. One intriguing development as of 2019 is the use of multi-sensor cameras in phones to increase quality while maintaining the small form factor. Some, not all, multi-camera designs use a monochrome sensor for sharpness and another for color. In the near future, the cost of entry into decent-quality multi-spectral imaging for someone who already owns such a phone may be very low indeed.

The 2013-2014 phase of the Jubilees Palimpsest Project (LINK) tested two techniques for integrating spectral imaging and reflectance transformation imaging. The simple technique used broadband visible (white) illumination from points around the hemisphere and a set of diffuse narrowband captures. The elaborate technique used a different set of narrowband captures at each light position around the hemisphere. The simple technique proved effective and in some ways superior. In rare cases, it may still be worth considering using narrowband illuminators at all light positions, such as when bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) is required for interpretation of material properties. For more information and the techniques tested, see the technical white paper (PDF).

The simple technique works because texture (not BRDF) is not wavelength dependent and spectral imaging is not texture dependent. Conventional RTI is concerned with texture and pays no more attention to color than the RGB channels of a DSLR camera. Conventional spectral imaging is concerned with color (differences in reflectance properties across wavelengths) and uses diffuse illumination to prevent influence from texture. RTI captures and renders the changes in highlights and shadows as a function of light position. The highlights and shadows as functions of light position are properties of luminance, and the variation in reflectance with wavelength is a property of chrominance. As of 2019, the simplest method of integration utilizes color spaces which distinguish luminance from chrominance, such as YCbCr. The YCbCr color space uses three channels to record luminance (Y), blue chrominance (Cb), and red chrominance (Cr). This color space can be easily converted to the RGB color space, which uses a channel for the brightness of each of three channels (red, green, and blue).

The combination requires image registration (meaning each pixel represents the same spot on the object for all captures), which is required of spectral and RTI separately. It would not be easily feasible to integrate spectral captures and RTI captures from different sessions or different cameras. The combination also assumes that the spectral captures have diffuse illumination, which is typical anyway. When it is difficult to capture images without glare or shine, a side benefit of Spectral RTI is the ability to create a perfectly diffuse monochrome image (by calculating the median luminance across all light positions).